My Experiences and Some Lessons of the 1971 War

Prelude

The 1971 war, and particularly the air war in the East, has been variously described as the finest moment in Indian military history after independence, as a blitzkrieg, and a lightning campaign that resulted in the birth of a new nation in quick time. However, in the euphoria of the victory, we have tended to overlook some of the important military issues and draw appropriate lessons from these. As students of military history and practitioners of air power, it is even more important for all of us to critically sift and examine even outright successes to separate the nuggets of gold that may have been lost in all the din and dirt. Herein, I would narrate some of my personal experiences and the lessons we could draw from these.

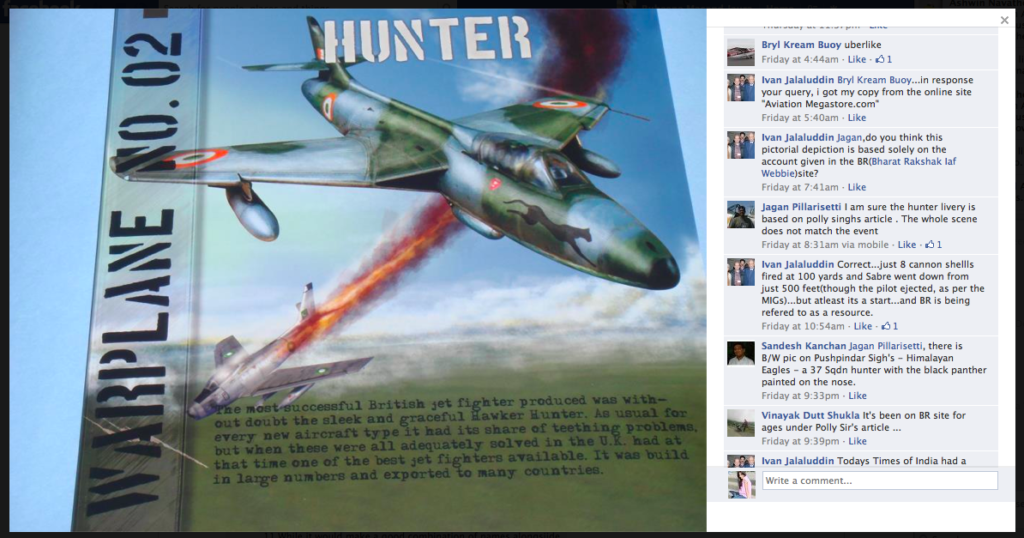

37 Sqn in 1971. The author is second from the left in the first row standing.

I was a young Flying Officer with very little experience, flying Hunters in 37 Squadron, The Black Panthers, from Hasimara in North Bengal when we went into action. As a matter of fact, you could call me one of the sausages produced in a factory as a result of the rapid inductions in the Air Force post-1962. Due to this, our course was given just 11 odd hours on Hunters in OTU in 1968, instead of the usual 50 hours, and sent to operational squadrons. In 1968-69, we had some 52 pilots each in both the Hunter squadrons in Hasimara against an establishment of 20, with me as the 35th in the seniority in 37 Squadron and little prospects of flying. How I managed to get some flying is another story. By December 1971, I had barely 240 hours on Hunters but looking at the positive side, our training was hard, and the slightest mistake or non-performance saw pilots grounded and on their way to ATC and controller courses. So, while the number of hours was meager, every sortie mattered in adding to the skill levels. On some other occasion, I would dwell on this aspect of training, which later helped me train my own subordinates, while identifying weak links thus maintaining high standards without any accidents and losses.

By May 1971, we had been put on alert and were standing by at 15 minutes readiness with four aircraft in a strike configuration, apart from the two aircraft on ORP, the latter being allowed an armed patrol at the end of the day. At the same time, our squadron had six of its aircraft modified for photoreconnaissance with three Vinten cameras, two side-looking F-95s and a forward-looking F-135 in the nose. Our new CO from April 01, Wg Cdr Suppi Kaul, who went on to become the Chief in 1993, had FR experience earlier and went about training some of us in this role in the prelude to the war. In this article, I will briefly go over just four important air operations, three that I was personally involved in, and the lessons we can draw from these.

Intelligence

Taking off from this training in reconnaissance, the first Issue I would touch upon is about intelligence gathering. Due to a quirk of fate and circumstances that form part of another story, Suppi Kaul chose me as his regular wingman for the war and we started reonnaissance missions inside East Pakistan from October 1971. Suppi Kaul and I did some nine missions before the war but only three of these were requested by the Army, one at Hilli, another over Dinajpur and, finally, the last one as late as the 02nd of December over Comilla & Lalmai Hills. One of these missions in early November saw me being given a Hunter till Gauhati and a helicopter with rotors turning to take the films to the C-in-C in Shillong but trudge back by bus to Gauhati after briefing the C-in-C. However, that is another funny story for another time. The Air Force also had a Sukhoi-7 Squadron at Panagarh and all Su-7s came with vertical cameras but these were also under-utilized by the Army as well as the Air Force, for reasons that are difficult to fathom even today. As a result, we ourselves went into attacks without adequate intelligence on the targets, with obvious wastage and losses. For example, for the first attack on Tezgaon airfield in Dhaka, we did not have any photographs of the airfield indicating the location of key installations or the likely dispersal areas. Because of this, we had to pull up and then look for suitable targets while the heavy ack-ack picked on the unlucky ones amongst us. On the 4th itself, we lost Sqn Ldr AB Samanta and Flt Lt SG Khonde from my squadron to ack-ack over Dhaka. I am certain the Army and the Navy had similar problems of inadequate intelligence because we did Comilla on a request by the famous General Sagat Singh of 4 Corps only on December 02. Suppi had gone to Command HQ in Shillong for a briefing on this mission on the 1st, and I got a call at night to bring two modified aircraft to Gauhati first thing in the morning. After a briefing by the C-in-C, who was also breathing down my neck while I prepared the maps, both million and quarter inch, we took off from Gauhati and landed at Kumbhigram around noon since we didn’t have enough fuel to get back. Suppi Kaul and I sat in the photo section developing and wet-marking 6000 prints till two in the morning sustained by a bottle of scotch given to us by a course-mate of mine on helicopters in Kumbhigram. We sent the photos to 4 Corps HQ at Teliamura by helicopter on 3rd morning before heading home to Hasimara. As would be obvious, this mission was a bit late for any planning particularly since 4 Corps had already started advancing on the 1st, as I learned later. On the other hand, we did a timely reconnaissance of Tangail and the area around well before the drop of 2 Para there on the 11th for checking out the drop zone. The lesson one can draw from this is that we need to keep gathering intelligence by fully utilizing all the resources so as identify the weak spots of the enemy and plan to hit them efficiently.

Planning of Counter Air Missions

The second issue is the way the counter air missions over Dhaka were planned by Command HQ. I was in the very first Mission 501, for air superiority on 4th morning after the formal declaration of war. This was an attack on Tezgaon airfield at Dhaka in a 3 aircraft formation with a Time Over Target of 0705 IST, 0635 East Pakistan Time. I was supposed to be Number 4 in the formation with Suppi Kaul leading the mission. With Sqn Ldr Allan ‘Mascy’ Mascarenhas as Number 3 falling out due to his aircraft not starting, I took his place as Number 3. Why I mention this seemingly minor issue is because in the formations we used to fly those days, the Number 1 and 3 had the liberty of initiating tactical maneuvering while Numbers 2 and 4 were required to stick, search and report. This became important later as we can only conjecture what Mascy would have done in the situation that unfolded. I have published the story titled ‘The 4th of December’ in brief about this raid in Bharat Rakshak and some distorted excerpts have also been printed in the book, ‘Eagles over Bangladesh’ for those who may want more details. Briefly, to draw the right lessons here, from Hasimara, we were attacking Tezgaon at 181 nm, which was 14 nm, or two minutes flying time each way, beyond our calculated radius of action of 167 nm at low-levels. Due to this, we had sacrificed our combat fuel reserves as well as some diversionary fuel and were ordered not to get into a fight. Two MiG-21s from Gauhati were to RV with us over the target and protect us from interception by Sabres. But then, Man proposes while God disposes, particularly in a war, so we got intercepted before the MiGs joined us, and I had to engage in combat with the two Sabres to save Suppi and his Number 2, ‘Billoo’ Sangar. In this, I was fortunate enough to shoot down the Sabre behind them and shake the other one off my tail to recover safely in Hasimara but with just fumes in my fuel tanks. Interestingly, I first got the Sabre in my sights beautifully at 400 yards, the perfect range for a shot, but young and inexperienced as I was, I pressed the camera button, having been trained so well in this area in mock combat. Fortunately, I realized this very quickly, lowered the gun trigger and shot him from barely 50 yards. However, having got embroiled in combat, I came back to Hasimara on a wing and a prayer with just fumes in my tanks despite having eased up to 15000 ft and maintaining range speeds on the way back. The lesson I drew from this engagement was to practice simulation of all switches for actual combat even in training sorties so as not to miss fleeting opportunities.

Our configuration for this lo-lo-lo attack was four 100 gallon drop tanks and 4×135 30 mm Aden guns. In all fairness, Command may have, perhaps, planned such attacks in the belief that, as reported, the Pakistani Sabres had been modified to carry Sidewinder missiles so a medium or high-level ingress was inadvisable. However, as we found out later this was faulty intelligence, which could have easily been confirmed from the PAF personnel who had deserted and joined the Mukti Bahini. As a matter of fact, the Sabres in the East didn’t seem to even have HE ammo for their air-to-air missions. Even if there was a doubt, we should have known the performance of the Sidewinder missiles from the reports emanating from Vietnam as also our own experience with the K-13 missiles on the MiG-21. Due to such doubts, I had actually raised the issue in the squadron and asked Suppi Kaul whether we expected the Sabres to be lined up out in the open waiting for our attack while we had taken the precaution of dispersing our own aircraft in camouflaged hard standings? In Hasimara, due to the vegetation, many people found spotting even the runway difficult after pull-up in simulated strikes. Also, if we didn’t spot any Sabres on the ground, whether peppering the runway with 30 mm cannons was worthwhile? Considering the numerical superiority we had over the lone Sabre squadron in the East, I had argued that we should go in large numbers at higher altitudes with bombs which gave us enough fuel reserves for combat as also some radar coverage from 509 SU in Shillong. If the Sabres came up to meet us, we could jettison the bombs and engage them in combat with numerical superiority aided by our MiGs with K-13 missiles. If they didn’t come up to fight, we could bomb the runways and other operating surfaces in steep glide attacks thus also minimizing our exposure to ack-ack. The Su-7s were also actually well suited for such attacks with the Russian M-62 bombs. This is what the Air Force finally did from 5th night resorting to steep glide bombing by MiG-21s from Gauhati, but after two wasted days and unnecessary losses. As stated earlier, my squadron itself lost two aircraft and pilots, Sqn Ldr Samanta and Flt Lt Khonde, to ack-ack over Dhaka on the 4th itself. Once again, better intelligence and planning could have helped us achieve air superiority faster with lesser losses.

Command of the Air

Due to such bombing of operating surfaces, from the night of the 6th morning of the 7th of December, there was no air opposition over East Pakistan. Such command of the air is what gave the Army the freedom to move rapidly in whatever manner it wished with impunity even in broad daylight. However, you may find some of your Army, and perhaps even the Navy, colleagues barely and rarely acknowledging it. This is a sad but true fact of inter-service rivalry and lack of understanding of air power in our land-centric military. However, the Pakistani General, AAK ‘Tiger’ Niazi, when asked why he surrendered though he had the troops to hold out much longer, clearly admitted that the main cause of the quick surrender was the Air Force. Pointing to the wings on Group Captain Chandan Singh’s chest, Niazi said, and I quote, ‘This had hastened the surrender. I and my people have had no rest during day or night, thanks to your Air Force. We have changed our quarters ever so often, trying to find a safe place for a little rest and sleep so that we could carry on the fight, but we have been unable to do that.’ Unquote.

As students of military history, we need to ponder over whether such command of the air would be achievable in any future conflict and also how to go about achieving it in the given circumstances. For this, during peacetime, we need to constantly revisit our doctrine, acquisitions and training to keep one step ahead of the potential adversaries.

That last reconnaissance mission over Comilla on December 02, also brings me to joint planning and cooperation issues. As mentioned earlier, we undertook that mission around noon on the 2nd, landing at Kumbhigram even while the lone squadron of PT-76s and troops of 18 Rajput were being attacked by Pakistani Sabres in that general area. We processed the films, marked the photographs till two in the morning, flying back to Hasimara on the 3rd after sending the films and prints to Teliamura by a helicopter. That is when I first heard about General Sagat Singh. All this time, we didn’t know that 4 Corps elements had already started their advance on the 01st without this intelligence that they had requested. While the Army-Air-Navy cooperation in this campaign was better than ever before, or after, I personally feel we could have done better in joint planning.

Let me give you another example. In late 1971, General Sam Manekshaw had called for a final presentation of plans. After the air force and naval plans were presented, he said, “That’s it Gentlemen, we seem to have everything in place”. While everyone started getting up to leave, Air Marshal Malse, the C-in-C of Maintenance Command quipped, with a smile, and I quote, ‘Sir, what about the army plans?’ General Manekshaw’s quickly retorted with, ‘Ahhh, how did we forget? We will have it tomorrow at the same time.’ I would take that a little further and state that it’s not enough to know each other’s plans. We have to jointly plan as many options, and contingencies as we can think of well in advance based on the capabilities of each service as well as the adversary. If that had been done in 1971 when we adequate time for preparations from March till December, we would have realized that air superiority in the East was a given and planned for rapid indirect movement of the troops to reach the center of gravity, Dhaka, as soon as possible with the least possible casualties instead of many frontal assaults while limiting the initial objectives to liberating only a portion of East Bengal where the Bangladeshi refugees could be resettled and a government formed. As would also be obvious, such an objective was fraught with serious future problems in terms of maintaining the independence of a part of erstwhile East Pakistan.

Heli-borne Ops & Use of the Indirect Approach

This brings me to the major heli-borne operations launched by General Sagat Singh commanding 4 Corps based in Agartala area. General Sagat seemed to be waiting just for such air superiority and used this dominance in the air immediately and brilliantly through maneuver by air, because of the riverine terrain, to get to Dhaka as quickly as possible. On the 7th evening itself, he heli-lifted 254 Gorkhas of 4/5 GR to a landing site near Mirpara South of the Sylhet Brigade with the rest of the battalion and supplies following through the night. Through a quirk of fate, with some intelligence failure on the Pakistani side, this single battalion locked up two Pakistani brigades in Sylhet till they surrendered. But then, fortune really favors the brave. On the 9th, he bypassed Ashuganj and Bhairab Bazar through another heli-lift of 4 Guards to Rajpura. While these two operations are the most talked of, he kept the helicopters busy till the last day lifting troops and supplies from Brahmanbaria to Narsingdi, Baidya Bazar and Narayanganj, to build his pincer on Dhaka from three different directions. In his bold utilization of barely 14 Mi-4 and a few Alouette helicopters, he was actively assisted by Group Captain Chandan Singh, Station Commander Jorhat, who had been specially attached to 4 Corps in this unprecedented cooperative effort. This again proves what joint planning and cooperation can achieve. Just the 14 Mi-4s flew over 1000 sorties lifting over 10,000 troops and about 400 tons of supplies in these 12 days. It also needs to be highlighted that Sagat’s task was limited to the east bank of the Meghna River and it was at his own initiative that he jumped across the Meghna bypassing the strong Pakistani defences at Bhairab Bazaar towards the center of gravity, Dhaka. Unfortunately, in a conservative military, such initiative was not really liked by some of the higher ups as evident from his reply to his Army Commander. I quote, ‘Jaggi, I am a Corps Commander. I am expected to exploit an opportunity. If an opportunity presents itself to cross the Meghna and give you an aim plus, I will take it. I am giving you the West Bank and beyond; you should be happy.’ Unquote. Despite being the architect of such a ‘Blitzkrieg’, if I may call it that, Sagat paid the price when he was overlooked for command of an Army soon after the war.

What was also surprising is that while Sagat of 4 Corps was planning such operations from the beginning and launched them as soon as air superiority had been achieved, the other two Corps in the East, 2 & 33, did not foresee such opportunities and did not even ask for such assets to leapfrog over strong defensive positions. So, while the coordination between the Services was better than ever before, or even later, it still showed a lack of joint planning and, perhaps, an understanding of the importance of air power and how it could be used in a given set of circumstances to expedite achievement of the objectives.

In this race to Dhaka, a mention must also be made of the para-drop of 2 Para at Tangail on 11th evening using a large number of Dakotas, Packets and AN-12 transport aircraft. 2 Para, under the command of its bold, aggressive, and flamboyant to boot, leader, Lt Col KS Pannu, also distinguished itself in moving rapidly towards Dhaka. After capture of the Poongli Bridge that evening itself, 2 Para along with other units of 101 Communication Zone raced to Dhaka from the North and were on the outskirts of Dhaka by 15th evening. It may need no reiteration that such a para-drop was made possible only due to the mastery of the skies in the East.

Psychological Warfare & Coup de Grace

The last important operation that I would like to mention is ‘the coup de grace’ from the air when we attacked the Governor’s House on the 14th when Governor Malik and General Niazi were having a meeting with all commanders and advisors. Acting on a timely piece of intelligence, it was amazing how quickly we reacted to the intelligence and were briefed on the location of the target from a Burmah Shell tourist map of Dacca that just happened to be in our Ops Room. We had four Hunters from 37 Squadron and four MiG-21s from Gauhati in this raid. The ack-ack was thick over Dacca even then and I vividly remember how we swooped down from 6000 feet in very steep dives to put our T-10 rockets and 30 mm cannon shells through the window of the conference room. Such unusual and untried but accurate attacks, without collateral damage, made sure that all of us came back without a scratch on us with spectacular results. General Shammi Mehta, C-in-C Western Command, then a Major commanding a squadron of PT-76 tanks under 4 Corps, later called it a ‘victory of mind over matter’ highlighting the importance of such psychological blows. The next day, on the 15th, we attacked the university area in Dhaka where, as per intelligence, the troops for the defence of Dhaka had taken shelter. Both these strikes expedited the surrender by General Niazi.

In this war, which has rightly been likened to a Blitzkrieg, we had surplus effort available for supporting the Army. After gaining complete command of the air, we sometimes sat on the ground waiting for demands from the Army. And, sometimes, we just got airborne on a search and strike mission beyond the known line of our forward troops. I mention this because even after almost 25 years of this war, it seemed we had not realized the value of secondary capabilities in our aircraft as evident from the questions of a very senior officer when I was put in charge of the MiG-21 Bis upgrade.

Conclusions

It may be obvious from all this that the lightning campaign for liberation of Bangladesh in just 12 days of all-out hostilities was made possible by three main factors. Firstly, command of the air achieved in reasonably quick time, even though it could have been achieved faster with fewer losses. Secondly, General Sagat’s bold and timely exploitation of control of the skies for heli-borne maneuver to knock on the doors of Dacca, the center of gravity of this campaign, in conjunction with 2 Paras under General Nagra’s 101 Comm Zone. Finally, the coup de grace delivered by the air attacks on Government House on the 14th while Governor Malik was holding a meeting with his cabinet and UN officials looking for a cease fire, and the University area on the 15th where the troops for the defence of Dacca were holed out. One only hopes that we draw the right lessons from this highly successful campaign.

Published On